The National Etruscan Museum, hosted in Villa Giulia in Rome, boasts the world’s largest collection of Etruscan objects and antiquities.

The history of the Etruscans is both intriguing and paradoxical. Almost entirely overshadowed by Ancient Rome, the Etruscans nevertheless gave early Rome its first Kings and engineers, who built the Circus Maximus and one of the world’s earliest sewage systems that helped drain the local marshlands. This paved the way for Rome to grow from an early hill settlement to a city with palaces and temples that would reign over the Western World.

The Etruscan influence ended with the expulsion of the last Etruscan King, Tarquinius Superbus, marking the end of the Roman Kingdom and the beginning of the Roman Republic. Even though the Etruscan civilization was ultimately entirely absorbed by the Romans, it greatly influenced their culture. The Etruscan language gave loanwords such as the Latin persona (person) from phersu and place names such as Parma. See: extinct languages of Italy.

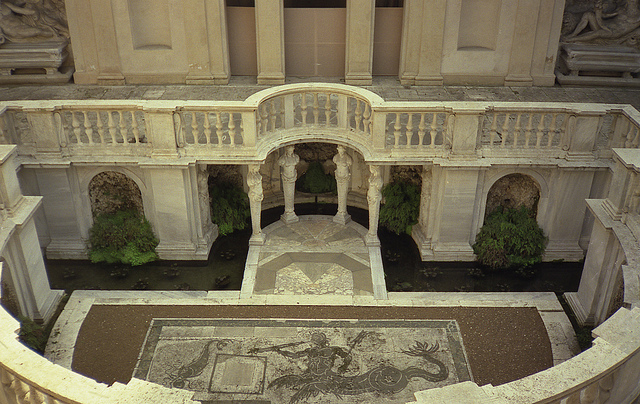

The charming, mannerist Villa Giulia itself is also worth a visit. It was commissioned by Pope Julius (Giulio) III and designed by Bartolomeo Ammannati, together with Giorgio Vasari and Vignola in 1551-1553.

The museum was created in 1889 with finds from the archaeological site of Falerii Veteres (now Civita Castellana, Lazio). The collection was later expanded with finds from excavations in Southern Etruria. Etruria covered an area corresponding roughly to Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio, bordered by the Tiber in the South and East and by the Arno in the North. Further donations and acquisitions such as the Barberini collection (in 1908), the Castellani collection (in 1919) and the Pesciotti collection (in 1972) make the Villa Giulia museum the world’s most important representative of the Etruscan heritage.

Etruscan art is particularly renowned for its figurative sculpture in terracotta (especially technically challenging life-size figures), cast bronze and metalworking (including refined jewelry).

The masterpieces of the collection include:

1. The bilingual Pyrgi tablets (500 BC)

The rare and unusual Pyrgi tablets are a real treasure, both from a linguistic and a historical point of view. What makes the tablets so special is that they are bilingual: two tablets are written in Etruscan and translated into Phoenician on the third one, making it possible for researchers to use the Phoenician version to read and interpret the otherwise undecipherable Etruscan. The tablets date from the beginning of the 5th century BC and are the oldest historical source of pre-Roman Italy among the known inscriptions. They record a dedication of a temple to the Phoenician Goddess Astarte (also known as Ishtar) by Thefarie Velanias, the ruler of Caere (now Cerveteri). From a historical point of view this attests evidence of Phoenician or Punic influence in the Western Mediterranean.

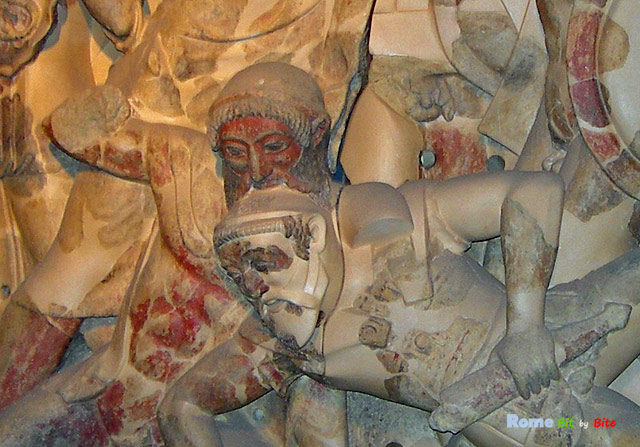

2. The reconstructed temple-relief from Pyrgi illustrating the myth of the Seven against Thebes (470-460 BC)

The temple relief from Pyrgi depicts the myth of the Seven against Thebes, the third play in an Oedipus-themed trilogy produced by Aeschylus in 467 BC.

A particularly gruesome detail of the temple relief shows Tydeus gnawing on the living brain of Melanippos in the course of the battle, when the armies of Polynices and Eteocles are fighting for Thebes.

3. The Sarcophagus of the Spouses (Sarcofago delgi Sposi) (530 BC)

The Sarcophagus is adorned with two figures representing a husband and wife on a couch as if they were at a banquet. Actually, while the object is generally referred to as the ‘sarcophagus’, its true function remains unclear. It may actually have been a large urn designed to contain the ashes of the deceased. We know that it is a funerary object because of the hand gesture of the woman, which reveals a ritual of offering perfume, which along with the sharing of wine, was a typical part of the funeral ceremony.

Unlike in Greek culture, where banquets were reserved to men, Etruscan women, who held important positions in society, were represented by their husbands’ sides, in the same proportions and in a similar pose, showing their equal status. The expression of the faces, the soft areas of their bodies, the almond-shaped eyes and long braided hair indicate Greek Ionian influence. However, the marked contrast between the high relief busts and the very flattened legs, and the preference for stylistic effects over anatomical accuracy is typically Etruscan. Instead, the hands and feet are particularly well rendered.

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses was made in the late 6th century, most probably by the same artist who made the Sarcophagus of Cerveteri, exhibited in the Louvre, Paris, which looks very similar.

4. The polychrome terracotta statues of Heracles and Apollo (c. 510 – 500 BC)

The over-life-size painted terracotta statues represent Heracles fighting the god Apollo for the Sacred Hind in the presence of Artemis and Hermes (however only the head of Hermes remains). Originally the statues were part of a four-figure scene representing one of the twelve labors (or dodekathlon) of the hero before his apotheosis among the divinities of Olympus. Discovered in 1916, the statues were commissioned by Tarquinius Superbus in about 510 – 500 BC to decorate the Temple of Veio in Portonaccio. It is attributed to Vulca, a famous Etruscan sculptor who was born in Veio.

5. The Chigi Vase

The Chigi vase is one of the most important examples of proto-Corinthian art. The vase or olpe is an ancient wine decanter made in Corinth in about (640-625 BC) and brought to Veio, where it was discovered in 1882. It is a unique exemplar of grecian polychromatic painting found in Italy.

The technique used and the black figures are typical of that time, yet the brown, yellow and white colors are not. Among the scenes depicted is the Judgment of Paris and a battle. Scenes depicted on objects of that period showing this type of complexity are usually considered high ceramic art.The artist, active between 640 – 630 BC, is known as the Chigi Painter (Pittore dell’olpe Chigi). However, some authors favor the appellation “Macmillan Painter” after the perfume bottle (aryballos) with lion-head mouth from the Macmillan collection exhibited in the British Museum in London, attributed to the same artist.

6. The Castellani jewellery collection

The Castellani collection features one of the finest collections of antique jewellery in existence.

7. The Cista Ficoroni

Heracles (right), Eros (center) and Iolaus (left). Foot of the “Cista Ficoroni”, an Etruscan bronze toilet box, 4th c. BC.

The Cista Ficoroni is a rare toilet and jewelry box used to store objects used for the care of the body. The cistae were usually cylindrical, with engraved decoration. The Ficoroni Cista, named after Francesco Ficoroni, an antiquarian who found it in Labico (now Lugnano) in 1738. It is the largest and most refined surviving example of a cista. Both the names of the artist and the person who ordered the cista, most probably as a wedding gift, appear in an archaic Latin inscription.

Photo credits (top to bottom): All photos © Rome Bit by Bite, except Villa Giulia first court by dalbera; Villa Giulia ninfeo by mmarftregjo; feet of the sarcophagus and Apollo statue by Klio; Sarcophagus by Fraaxe; Cista Ficoroni by Haiduc; Cista Ficoroni by Sailko;